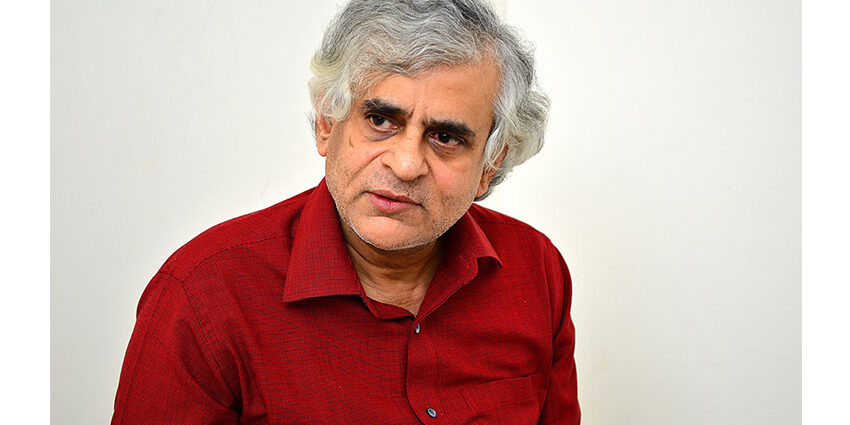

At a recent event, celebrated journalist and iconic rural affairs expert P Sainath spoke about the failure of the mainstream media to effectively cover the migrant labourer crisis and rural affairs.

Sainath, who was the Rural Affairs Editor of The Hindu, is the Founder Editor of People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), an acclaimed digital platform that primarily focuses on rural journalism. A recipient of the Ramnath Goenka ‘Journalist of the Year’ Award, Sainath was hailed by Amartya Sen as “one of the world’s greatest experts on famine and hunger”.

The University of Alberta honoured Sainath with the Honorary Doctor of Letters degree (DLitt). He was also the McGraw Professor of Writing at the University of Princeton. His best-selling book Everybody Loves a Good Drought, published in 1996 by Penguin Books is considered one of the finest texts on rural poverty and farmers’ distress.

P Sainath had to lot to say vis-à-vis how the media behaves and what ails the mainstream media.

Migrant Labourers and Indian Media

Let me begin with a small exercise for those who are aspiring media persons, journalists and researchers. Do a research of the Indian mainstream media over the past 10 years if there is any coverage about migrant labourers. It can be in any of the media platforms – print media, television or digital media. Find me a series or a particular coverage or a panel discussion or anything in any newspaper or website or news channel that entirely focused on them. I am not talking about any opinion piece or a passing reporting. Rest assured you will not be getting one. You might find it in The Hindu between 2011 and 14, but mostly you can’t. According to the 2011 Census, 28 per cent of the total population are migrants. The mainstream media hardly knows about the many kinds of migration occurring in India.

Migrant Labourers and Indian Media in the Covid-19 Situation

As the Indian national or so-called mainstream media had no connection with migrant labourers, workers and the poorest Indian citizens, that’s why, in this pandemic situation, they just have no clue about them. How many are they, where they came from, where they want to go, are totally unknown to the mainstream media. Neither the census nor the national survey of India shows interest about them. We never gave any coverage to them. I am also a part of this media that I am criticizing now. I spent around 35 years in the industry. I don’t know how we call something mainstream media when it excludes the mainstream.

Rural Coverage by Mainstream Media

In average, the Indian newspapers or national dailies devote only 0.67 per cent of their front page to cover the Indian rural sectors over the past five years. Centre for Media Studies in New Delhi, the oldest media monitoring organisation of the country, said that this is 0.67 per cent because there are election campaigns in these five years. When there is an election, the percentage might change to 5 per cent to 8 per cent. But on average, it is just 0.18 to 0.24 per cent of the coverage that is given to rural affairs by the national media.

In 2022, the Indian press will cross its glorious 200 years. Raja Ram Mohan Roy was one of the founders of Indian journalism. He and many great persons of his time focused on the have-nots. But in the last 25 to 30 years, the Indian media is continuously disconnecting itself from the common public – those who are poor or marginalized – as they have no purchasing power and they can’t buy the product of the advertisements, which is the main concern of the media.

In 2006, the young reporters of The Times of India in Mumbai approached their leaders that they should cover the farmers’ suicide and many more rural issues but the authority said that the dying farmers do not buy The Times of India but an elite of south Bombay does. In 30 years, the media has reduced journalism to a revenue stream.

I will cover you if I make money to cover you is the principle that the mainstream media has now. In 1988, when I joined as a journalist, there was a labour employment correspondent. Today, if there is anyone on this beat, he or she will be named as industrial relation correspondent. The media talks about the industry but not about the workers of the industry. When it is called agriculture affairs, it is not that the reporters are covering the farmers. In fact, the reporters are covering the agriculture ministry and business.

The reporters sang the saga of the ruling agriculture minister, which was prominently seen in the case of Sharad Power. Now you don’t even know the name of the agriculture minister. You only know about the Prime Minister and the Home Minister. Thus, we have landed in a mess with no clue. When we needed more journalists on the field from March 25, Hindustan Times laid off 1,000 reporters and The Times of India started giving half the salary. Thus, journalism is getting ruined. People’s Archive of Rural India has been covering these issues from 2014.

Future of Migrants

When a migrant worker is returning home these days, at first, they have to deal with the police as they should go to the quarantine. The government took very few initiatives for their quarantine camps. They are being made to stay in the field or in open places in the summer, where they are dying of non-COVID-19 deceases.

To find work, they left their homes but now they are returning. Now, they will be in agriculture where there is already high pressure. Statistics say that around 122 million people lost their jobs. Food crops and vegetables remain unsold. Even the handloom handicraft industry, which is the second biggest employer, has been suffering. You name a profession and I shall say that they are in severe trouble.

The Government of India has failed miserably to handle this Covid-19 situation. In the total period of lockdown, the Prime Minister addressed the nation five times and only in his last speech did he finally name the migrant labourers.

Not all the journalists of the media industry are forgetting journalism. There are many good people in this sector, which I am criticizing. In Mumbai and Chennai, many reporters have tested positive for Covid-19 while they were doing their work.

To get some relief, at first, farmers have to secure their Kharif food crops. We have to enlarge the NREGS (National Rural Employment Guarantee Act). People will come back because they have no option left. We need to build a great National Health System.

The author, Trina Chowdhury is associated with Adamas University Media School